Water. Always difficult to write something original about it, but let’s spend again a few words in celebration of this molecule. Water is present, or can be inserted in many porous hosts, like zeolites or MOFs. Not all of them love water. This time the question was: what does water do inside channels of similar size but different hydrophilicity?

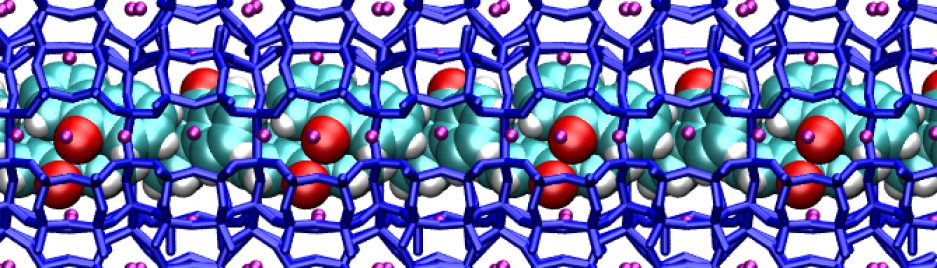

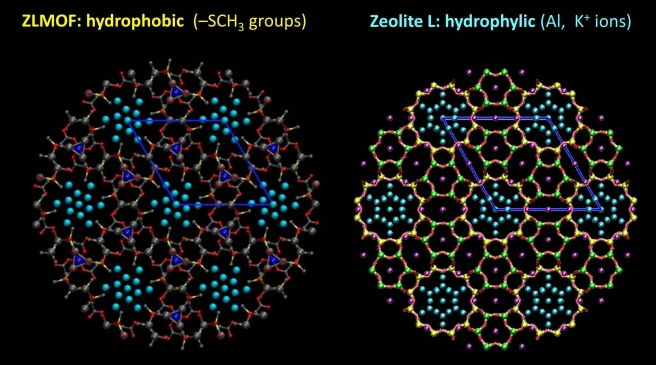

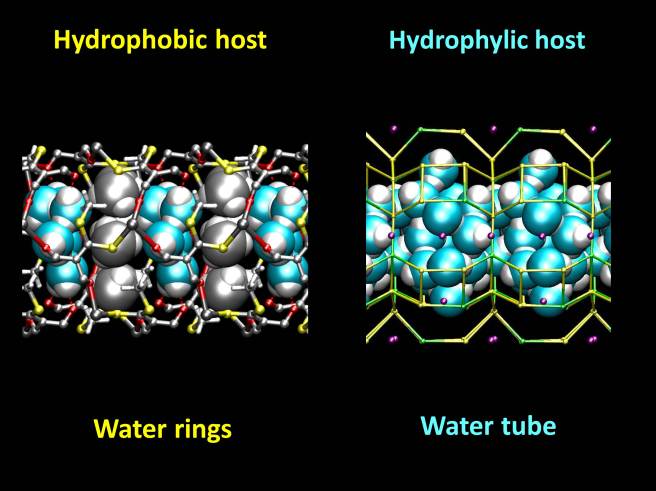

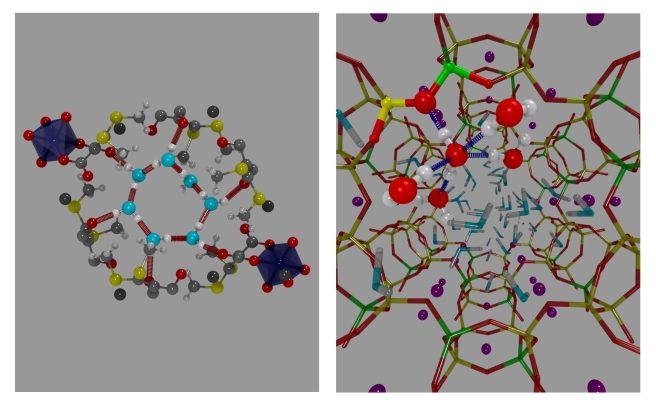

We modelled the behaviour of water in two porous materials. The first one is zeolite L, which is hydrophilic. The second one is a metal organic framework, or MOF, which has pores of similar size, but less affinity to water. Our starting point was the X-ray structure of the two materials, shown below.

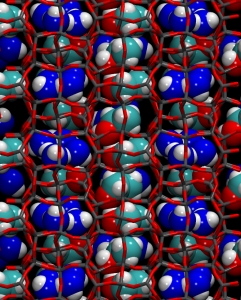

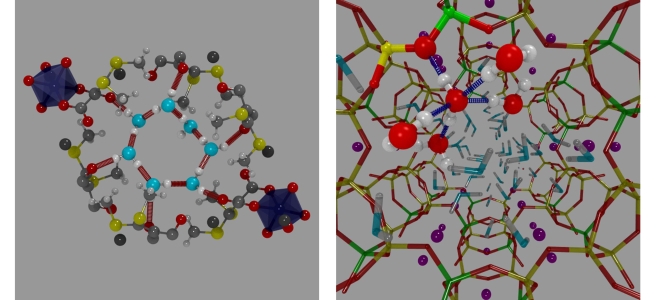

The water distribution inside the pores looks very nice and symmetric. Unfortunately, the water positions are only partially occupied. So, by using the experimental water content as input, we optimized the structure of these materials, and here’s what we got.

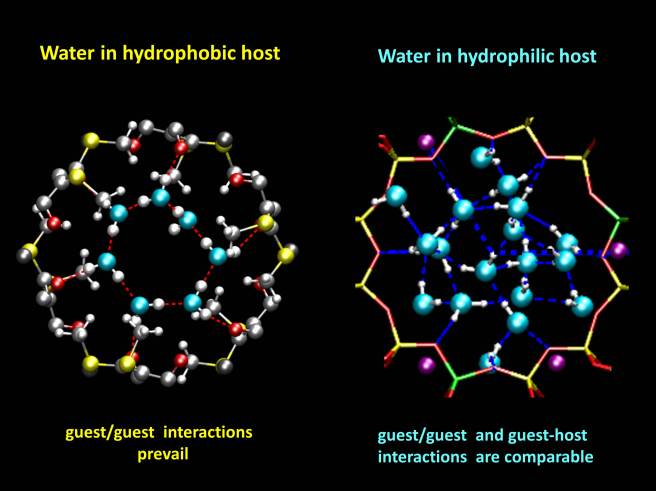

We found that water stabilizes both materials, and that the shape of the water clusters inside the channels depends on the affinity of the hosts to water.

While the hydrophobic host contains water rings, kept together by water-water hydrogen bonds, the hydrophilic host contains a continuous water tube, stabilized by interactions with the zeolite and also by hydrogen bonds.

In the zeolite channels, some water molecules are surrounded by five strong hydrogen bonds. This structure is similar to water pre-dissociation complexes found in liquid water, and it might probably explain the high proton activity found in zeolite L.

Zeolite L is a promising material for solar cell applications, but the high proton activity inside the channels might damage some of the organic dyes that are incorporated as guests. Now we have identified a possible cause of the problem, and this might be a first step to improve the performances of these materials. Also, we hope that the atomistic insight on the water rings inside the MOF could help to exploit this material as host matrix for new compounds.

Personally, I much enjoyed doing this work: there’s always something to learn about confined water! The “driving force” for starting this work was an invitation, so many thanks to Michael Fischer and Robert Bell for organizing the Special Issue “Modelling Crystalline Microporous Materials” in the Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. If you like porous materials and #compchem, please have a look at this issue, it has many beautiful contributions. Also, thanks to ChemRxiv for hosting our preprint, and to the 2019 Twitter #RSCPoster conference, where this work was first presented as poster.